Re-thinking human progress. We’re (no longer) all in this together…

Saying the world needs a new way to measure economic success is like saying we must end poverty. A true, but bland, statement that abrogates responsibility for the actions needed to make it happen.

Indeed we, collectively, must do something. But the scale at which most of us operate and our access to the levers of power make it difficult to understand what we should do, or how, if we even try. Not to mention the complexity of attempting to unravel a global standard that has done more to advance human progress over the last 70 years than any other economic theory before it.

But try we must. Abandoning economic growth as the leading global indicator is more than about deferred responsibility and lofty negotiations between world leaders about how to manage the economy. Switching to a metric other than growth as a single measure of economic success will directly impact how we run our lives and how we plan and save for our, and our children’s, future.

In a world that has been turned upside down by a global pandemic it’s now clearer than ever as to why it’s time the tables were similarly turned on the closed-door world of econometrics. If in doubt you might try to answer these three questions:

1. What does it mean that the S&P 500 is at, or near parity with pre-pandemic levels (when 40 million joined the ranks of unemployed in the US since the pandemic took hold)?

2. (The recent pandemic to one side) over the last decade the human race has been wealthier, living longer, and less likely to be living in poverty than at any time in human history – so why is trust in government and a feeling of economic security, in some of the world’s richest countries falling?

3. The explosion in digital technology has put more information at our fingertips than ever before – so why is it getting harder to predict what’s happening around us and – by default – the future?

A measure of a future past.

So what is happening? Growth – or rather the use of GDP as a means of measuring it – was first defined in 1934 and later adopted at the Bretton Woods conference of 1944 to help with global economic reconstruction after World War II. It’s fair to say therefore it was designed for a time of human scarcity – where modern manufacturing and the production line enabled, designed and built the consumer society. Quite literally a world where more equalled more – mathematically, consumption = happiness.

“Economic welfare cannot be adequately measured unless the personal distribution of income is known. And no income measurement undertakes to estimate the reverse side of income, that is, the intensity and unpleasantness of effort going into the earning of income.

Distinctions must be kept in mind between quantity and quality of growth, between costs and returns, and between the short and long run. Goals for more growth should specify more growth of what and for what.”

Simon Kuznets, economist – 1934 & 1962

In 2020 that production line future is no longer our present experience (see Flag 2 below). Firstly, digital has changed the nature (and concept) of production. We no longer have to wait for the next new model to roll off the line. Digital products are in a perpetually unfinished state and consumers get them on demand or even automatically. Indeed such is the confusing nature of modern commerce that we , as individuals can now be producers, consumers and products simultaneously.

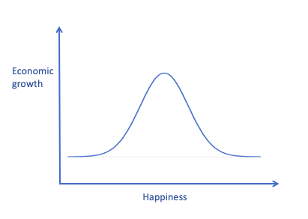

Secondly, the connection between growth (as the economic definition of happiness) and consumption is broken. Plotted on a graph the two attributes start to look more like a bell curve than an infinitely ascending straight line as the pursuit of growth assumes – as acquiring more ‘stuff’ delivers diminishing returns in personal satisfaction and puts more pressure on individuals to earn or spend more to keep up with their peers (Flag 1 below). As rioters in Hong Kong, in contrast to their newly-urbanized neighbours in mainland China bear witness – our priorities as individuals shift above a certain level of earning and consumption power.

Flag 1: It can’t go on forever

Measured against growth consumption delivers diminishing returns in human happiness

Throwing the baby out…

It’s not heresy to say this. The creation of the World Happiness report by Jeffrey Sachs’ at Columbia University’s Earth Institute, the appointment of a Minister for Happiness by the government of the United Arab Emirates, and the world’s first “Wellbeing Budget” announced by New Zealand in 2019 show how the ground is shifting and the direction it’s moving. And Katie Raworth’s Doughnut Economics model shows how we might rethink economics to balance economic necessity with environmental safety – Meet the doughnut: the new economic model that could help end inequality, World Economic Forum 2017 https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2017/04/the-new-economic-model-that-could-end-inequality-doughnut/

Waiting for practical “trickle-down” from a handful of governments and think-tanks however is not enough to alleviate the pressures that are building in the system now. The free market – the primary driver of human progress for much of the last century is starting to destroy it.

With income inequality across the West now at its highest since the last World War, the stock market, instead of acting as an efficient distributor of wealth across whole populations has become a closed club – defending the interests of those that own the companies traded on them – as separate, and distinct, from the interests of those that work for them or consume the products they sell.

Nor is saying that the age of growth is over about anti-market ideology. A market that protects the few in spite of the many ceases to be a market by definition – and will shrink as distrust and suspicion turn people away in search of more competitive, or equitable, alternatives.

So much, so gloomy.

But this is not our point. Despite the sombre mood around the world. Another way is emerging, providing breadcrumbs that show a new path that could help steer us away from the gathering storm.

Along with the many other firsts that have been attained since the dawn of the 21st Century is one that goes unnoticed. Despite concern around the power and influence of social media (often rightly so) – its ability to set the agenda has a valuable trade off, if it can be used collectively to positive effect, if combined with the other side-effect of the digital revolution – the massive availability of real-time data.

A wordy way of saying that the stories we tell ourselves, the stories we use to unite humanity and improve the human condition already no longer depend on our leaders. Indeed, you might say that the era when governments lead is coming to an end.

The challenge ahead of us of course is to find a way to agree what stories we should tell – and which we should listen to. The stakes are high. A more flexible perspective of what constitutes economic success would enable us to re-engineer the political economy for the century ahead – and give us the power finally to end poverty, and save the environment, in the process.

So where do we start? Firstly, wider and wider availability of digital technology, and the real prospect of it being universally available within our lifetimes, can give us the direct power to set the terms of reference – by helping us to gather more data which we can use to measure our progress towards achieving desired outcomes. In the language of computing – to measure the effects given the cause. Something that our obsession with growth is no longer able to offer.

Change is coming

Secondly, in the absence of global leadership, the private sector, especially those in the innovation economy are in a strong position to drive adoption of new models and push the envelope towards a new way to measure company and staff performance.

It might not feel like it for many of us, but change is happening. One of the surprising upsides of the financial crash in 2008 and the subsequent growth in shadow banking and private capital markets has been the rapid expansion of the start-up economy that also coincided with the collapse in the cost of technology.

In the absence of predictable earnings (in fact, despite the highly unpredictable future of most start-up firms – see question 3 above) employees at many startup companies receive stock or equity in the companies they work for. It can be an equitable trade-off – the company gets to attract and keep good people; the employees get to share in the success of the firm they’re helping to build.

Currently around 14 million US employees have some equity in the companies they work for as part of their compensation packages – One way to close the wealth gap – make employees part owners, Fast Company, October 2019 https://www.fastcompany.com/90346767/one-way-to-close-the-wealth-gap-make-employees-part-owners

There’s nothing new or revolutionary about this way of rewarding staff except perhaps one of scale. If we’re serious about moving towards a form of economic management where more of us feel a sense of “ownership” from our work and what we do then systems like this, or similar, will need to be adopted and introduced at a massive scale.

Currently, the multiple pressures unleashed by the growth of the digital economy and the aftermath of the pandemic – from more remote working to new forms of employment – suggest that there’s no alternative to some form of ownership model to build successful companies, and more importantly, healthy societies.

Pay me now. Reward me later.

The impact of compensation structures like this is about more than cynicism or cosmetics so that employees work more for less pay. While stakeholder ownership structures are proven to result in employees that work harder, in the long-term they also earn more on average, and are less likely to leave (an imprecise but possible indicator of their greater satisfaction with the work they’re doing).

This kind of structure works both ways. Compensation that is not solely linked to short-term earnings or quarter-on-quarter growth incentivises companies to think about the longer-term – encouraging responsible behaviour and forcing them to align more closely with the aims, objectives and lifestyles of the people they work so they can attract the best staff.

Of course, widespread adoption of new ways to incentivise employees and manage markets is easier in principle than in practice. The realities of the digital economy pose some very challenging questions – what does it mean that a worker can be at once manufacturer, employer and employee? And who decides how they should be rewarded, protected in the event of a downturn, or managed to ensure they meet environmental or ethical standards?

The massive increase in investment into goal-driven investing – such as funds that track companies progress in meeting ESG (environmental, sustainability and governance) goals are proof that metrics beyond the simple measurement of profit can be powerful forces, incentivising companies to steer a longer-term path – Sustainable investing is set to surge in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic, CNBC, June 2020 https://www.cnbc.com/2020/06/07/sustainable-investing-is-set-to-surge-in-the-wake-of-the-coronavirus-pandemic.html

Own goals?

Imagine how much more powerful it would be if we could harness the data-analytics capabilities of digital to track performance across a much wider range of metrics and larger numbers of firms – including start-ups and off-market companies.

The outcome would surely help lead us to a more accurate definition of sustainability – not to mention a more nuanced understanding of how to define success in the twenty-first century, and the levers we need – government, regulatory and financial – to make a more sustainable world possible.

Change is difficult – especially in the absence of global consensus or leadership by governments – but by working together the private sector, especially technology companies and firms with an innovation culture, where data gathering and analytics is almost second nature – has the power to influence how success is measured and how rewards are earned. The benefits could be epoch-defining – happier workforces, more efficient income distribution, and a significant contribution to changing the dialogue around what constitutes human progress. Only by telling ourselves a new story can we take hold of the reins of humanity so that we learn to pull together. The power to tell it is already within the reach of business leaders everywhere. Let’s hope they can come together to realise it.

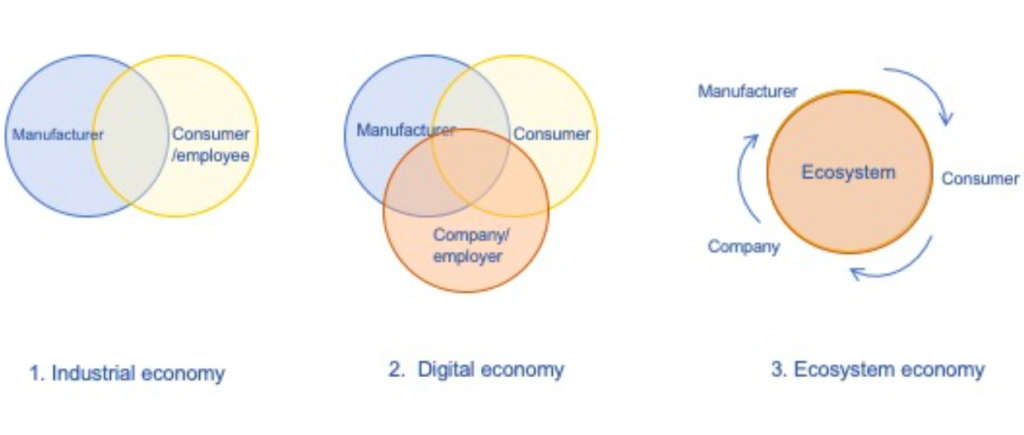

Flag 2: New model economics

The digital economy is more complex than its 20th century predecessor

The model of the modern industrial economy can be described visually as set out in figure 1. above – where employees were connected to their employers as workers and consumers. The digital economy has introduced a new dimension where producers of goods are distinct from the employer and the employee can be both product, employee and employer. The circular or ecosystem economy model – where everyone is included, dividends from success are more evenly shared, and nothing is wasted from the system – is shown in figure 3.

The jump from 1. to 3. is big. Not just conceptually – it requires international coordination between governments, business and citizens to work together. The private sector – particularly early-stage and digital firms – can play a role in the transition by more widely deploying a model built around wider distribution of asset ownership (figure 2) backed by data that enables “success” to be measured from multiple perspectives.

For more information and insight – join our global briefings series as we talk to fintech founders, ecosystem partners and institutions on the impact of coronavirus, and what comes next. www.findexable.com. Download The Global Fintech Index 2020 City Rankings on http://bit.ly/2020GFI